Adapted from Cultural Maturity: A Guidebook for the Future

How do best talk about how culturally mature perspective alters understanding? Most simply, such perspective lets us more directly address life’s bigness. But we need more precise ways to speak about it. Our question is part of an important larger question. Cultural Maturity’s cognitive changes not only produce new conclusions and change how we think they alter our understanding of what makes something true at the most basic of levels. We need to better understand just how this is so.

We can come at making sense of how Cultural Maturity’s changes alter our understanding of truth itself in multiple ways, each with its lessons to teach. One of the most useful draws on a basic observation: Needed new understandings of every sort require that our thinking create links, “bridges”—and not just between phenomena we’ve regarded as different, but often between things that before now we’ve treated as complete opposites—as polarities.

F. Scott Fitzgerald proposed that the sign of a first-rate intelligence (we might say a mature intelligence) is the ability to hold two contradictory truths simultaneously in mind without going mad. His reference was to personal maturity. But this capacity is such an inescapable part of culturally mature perspective that we could almost say it defines it.

Effective global policy requires “bridging” ally and enemy. It also bridges political ideologies and, in the end, even usual ideas about war and peace. Mature gender identity and love link masculine with feminine, and individuality with connectedness. New approaches to leadership create bridges between leaders and followers, and as needed greater transparency occurs, bridges also appear between the internal worlds of organizations and between organizations and the larger world. The needed new kinds of relating, values, and understanding don’t require that we consciously recognize that bridging is taking place, or even that polarities are involved. But they do require that we somehow get our minds around a larger picture and act from it. (My 1992 book, Necessary Wisdom, uses this simple observation as a lens to examine a broad array of contemporary issues.)

We can think of Cultural Maturity’s point of departure as itself a bridging dynamic: We step back and see the relationship of culture and the individual in more encompassing terms. Cultural Maturity bridges ourselves and our societal contexts (or put another way, ourselves and final truth). It is through this most fundamental bridging that we leave behind society’s past parental function.

It is important that we not misinterpret this. Cultural Maturity is not about culture’s role disappearing. Rather it is about a new and deeper recognition of how individual and culture relate—about how, through our thoughts and actions, we create culture, and how personal and cultural realities each inform the other. It is also about making our understanding of both being an individual, and being an individual who lives in an interpersonal context, more dynamic and complete.

This most encompassing linkage holds within it a multitude of more local “bridgings.” Nothing more characterized the last century’s defining conceptual advances than how their thinking linked previously unquestioned polar truths. Physics’ new picture provocatively circumscribed the realities of matter and energy, space and time, and object with its observer. New understandings in biology linked humankind with the natural world, and by reopening timeless questions about life’s origins, joined the purely physical with the organic. And the ideas of modern psychology, neurology, and sociology have provided an increasingly integrated picture of the workings of conscious with unconscious, mind with body, self with society, and more.

Recognizing the fact of polarity by itself is not new. Our familiar Cartesian worldview is explicitly dualistic. Nor is the idea that polarity might be pertinent to wisdom new. That is, in fact, a quite ancient recognition. Epictetus observed that “Every matter has two handles, one of which will bear taking hold of, the other not.” But what I describe here is new, and fundamentally.

In modern times, even if we have acknowledged the basic fact of polarity, most often we’ve missed that the sides of polarity might relate. And certainly we’ve missed that they might relate in ways that produce today’s needed more mature and complex picture. We’ve assumed that it is right to think of minds and bodies as separate even though daily experience repeatedly proves otherwise. And we’ve accepted that a world of allies and “evil empires” is just how things are even as one generation’s most loathed of enemies becomes the next generation’s close collaborator.

The fact that we could miss polarity’s larger picture might seem odd. Why would we assume that reality is anything but whole? It turns out that there is a good reason. In fact, polar perception has an essential developmental function—in human change processes of all sorts. Indeed, it is critical to the mechanisms of development.

Appreciating the key role projection has historically played in human understanding helps us make the connection—both with regard to polarity’s role in times past and to precisely what changes with maturity. Projection involves polarity, a fact that becomes particularly tangible when mythologizing’s ardencies are involved. Projection in times past has served us. But one of the things that most marks Cultural Maturity is how its changes help us get our minds around the larger relationships that projection has kept us from recognizing. Mature thought in our individual lives does so in an important but circumscribed sense; culturally mature thought does this with regard to understanding more generally.

Implied in all of this is the essential recognition that the “problem” with polarity is not an intrinsic difficulty. Rather it is an expression of where we reside in the story of understanding. In times past, polarity worked. The polar tensions between church and crown in the Middle Ages, for example, were tied intimately to that time’s experience of meaning. With the Modern Age—and just as right and timely in their contributions—we saw Descartes’ cleaving of truth into separate objective and subjective realities, along with the competing arguments of positivist and romantic worldviews. And while here I’ve strongly emphasized the outmodedness of petty ideological squabbles between political left and political right, I am just as comfortable proposing that such squabbles, in their time, were creative and essential. They drove the important conversations. The problem is not with polarity itself, but with its inability in our current time to effectively generate truth and meaning.

If the relationship between “bridging” and complexity is to make ultimately useful sense, we must take care to avoid confusing “bridging” in this sense with a couple more familiar outcomes. Bridging as I am speaking of it is wholly different from averaging or compromise, walking the middle of the road. And just as much it is different from simple oneness, the callapsing of one pole into the other as we commonly see with more spiritual interpretations. Bridging, as I use the word, is about consciously engaging the larger whole-ball-of-wax picture.

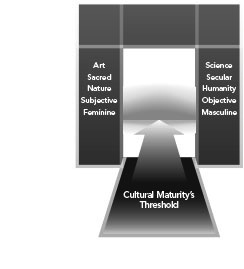

I often make use of a simple diagram to emphasize these differences. It depicts Cultural Maturity’s threshold as literally a doorway, with each side of the doorway’s frame representing one half of a polar relationship.

“Bridging” and Creative Truth

But a further filling out of how polarity’s work has particular importance for understanding where Cultural Maturity’s changes take us. We find that polar relationships reflect a specific kind of symmetry. Put simply, conceptual polarities have complementary right and left hands. With polarity’s right hand we find harder, commonly more rational and more material, qualities. With polarity’s left hand we find qualities of a softer, more poetic, and often more spiritual sort. Facts juxtapose with feelings, mind with body, matter with energy, and so on.

Psychology has terms for these extremes, drawn from the study of myth. It refers to the more concrete side of each pairing as “archetypally masculine,” and its softer counterpart as “archetypally feminine.” The gender-linked language can cause confusion, particularly today as women and men each seek to make both poles their own, but its sexual connotations are evocative and in a way particularly pertinent to our inquiry. In some fundamental way, the relationship between polar extremes becomes “procreative.”

An appreciation for such symmetry assists us most immediately by helping us flesh out systemic relationships of the here-and-now “multiplicity” sort. For example, we can understand a lot about opposing conservative and liberal tendencies in the political arena by thinking of them in terms of juxtaposed archetypally masculine and archetypally feminine tendencies. On the Right we find harder, more difference-biased values—competition in the marketplace, a strong military, the integrity of national borders, and rugged individualism. On the Left we find values of a softer, more relationship-biased sort—identification with the disadvantaged, government as advocate for the common good, environmentalism, and equal rights. It is a simplistic approach that leaves out a lot, but it also provides useful insight.

Later in the book, I will make use of other here-and-now multiplicity observations that similarly draw on this fact of underlying symmetry. For example, I will apply this recognition of symmetry to help us identify and map common conceptual traps. Observations in the previous chapter about how familiar systems notions fall short illustrate this kind of application. I described how systemic understanding as we have known it sides variously with more engineering truth or more spiritual and poetic truth. We could equally well talk of the difference in terms of identification with more right-hand or more left-hand sorts of truth.

This recognition of underlying symmetry also has critical implications when it comes to “multiplicity” discernments of the more temporal sort. While polarities at every cultural stage juxtapose right-hand and left-hand sensibilities, these juxtapositions evolve in predictable ways. In the next chapter I will describe in more detail how this works. For now we can note that over the course of history we see a gradual progression from times in which archetypally feminine values—connection with nature, tribe, or spirit (values that emphasize oneness)—most defined truth, to a reality in our time in which archetypally masculine values—individuality, materialism, competition, or the logic of science (values that emphasize separateness)—have come to play a much larger role. Later we will examine how this progression helps us understand Cultural Maturity as a time in history—how Cultural Maturity’s changes fit into culture’s larger story, why they involve the new capacities I have described, and why in our time theses changes has become essential.

Appreciating the role of polarity in understanding provides one of the best ways to begin to grasp the power of a creative frame. I’ve proposed that if we can successfully answer a series of polarity-related questions, we have made it most of the way toward what is needed to develop effective culturally mature conception. Those questions: Why do we humans tend to think in the language of polarity in the first place? Why have we now begun to see understanding that bridges familiar polar assumptions? And how do we best think about what happens when we do bridge polarities?

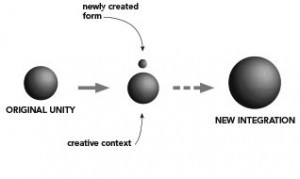

A creative frame provides answers to these questions. Let’s take them one at a time. First, why do we think in polar terms in the first place? Creative Systems Theory proposes that polarity is essential to the workings of formative process. Creative change begins in a womb-world—in original unity. The newly created thing then buds off from that initial wholeness, creating polarity in the process. Over time, the newly created thing, and polarity with it, evolves and matures, with polarity manifesting in predictable forms with each creative stage.

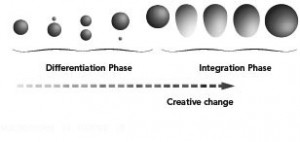

A creative frame also addresses the second question, why now we might see the bridging of past polar assumptions. Bridging plays an inherent role in creativity’s workings. We can think of the underlying progression of any formative processes as having two halves distinguished by polarity and our relationship to it. The creative stages that bring new creation into being represent only a start. Any creative process has a differentiation phase and an integration phase. Once new possibility has become established in a human mind or minds, that possibility reengages with the context from which it was born, becoming part of a newly expanded whole. The person or group then experiences this now-expanded whole as “second nature”—as the new common sense.

Polarity and Bridging in Formative Process1

We recognize this two-part progression with creative processes of all sorts. When I myself have a fresh insight, at first I find excitement in its newness. It becomes something separate and distinct, and in this distinctness grows and evolves. Then, with time, I begin to experience it differently, as simply one part of a new, expanded me. When an innovative idea first arises in a culture, it creates excitement and controversy. It is something new and unique. Then, gradually, having been challenged and having matured, the idea can become an accepted part of a now-expanded cultural reality. Creation begins in oneness, becomes manifest through polarity, and then reconciles into a larger, more inclusive entirety. Creative Systems Theory proposes that the fact that we are now beginning to think in ways that recognize larger systemic relationships is a product of this second creative mechanism.

Creative Systems Theory describes how we can extend this simple picture of polarity’s evolution to reflect creative stages over the course of formative process and use the result to develop detailed maps for delineating change in human systems—including culture’s larger story. Creative Systems Theory describes how both the way truths of times past were seen as existing in separate polar worlds and the fact of understanding symmetry are products of this ultimately creative mechanism. It also describes how the different ways polar opposites relate at different times in culture’s evolution—including how the relationship between polar opposites is changing in our time—have similar origins. The answer to the third questions—what happens when we bridge polarities—has informed all of this threshold task’s reflections on truth, and the book as a whole.

The Creative Function